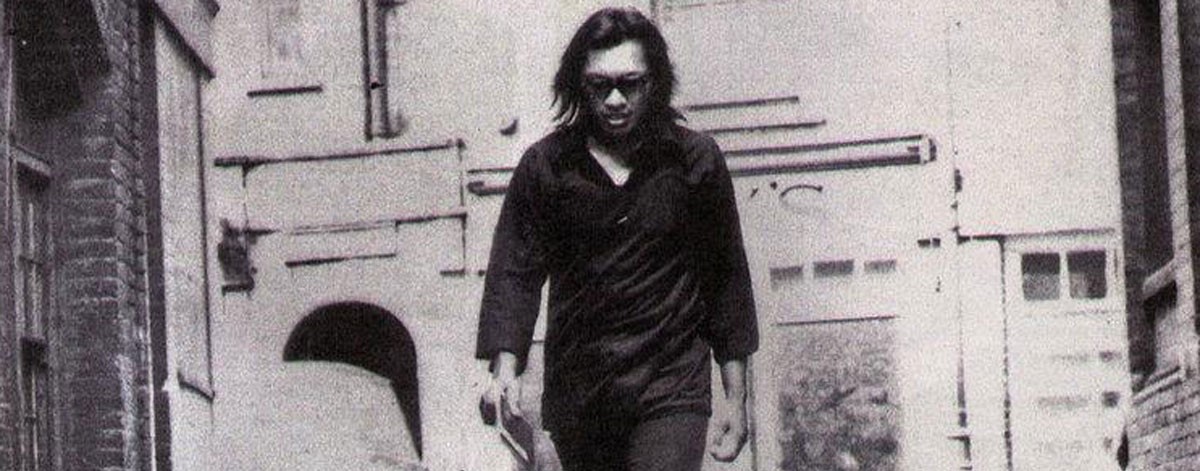

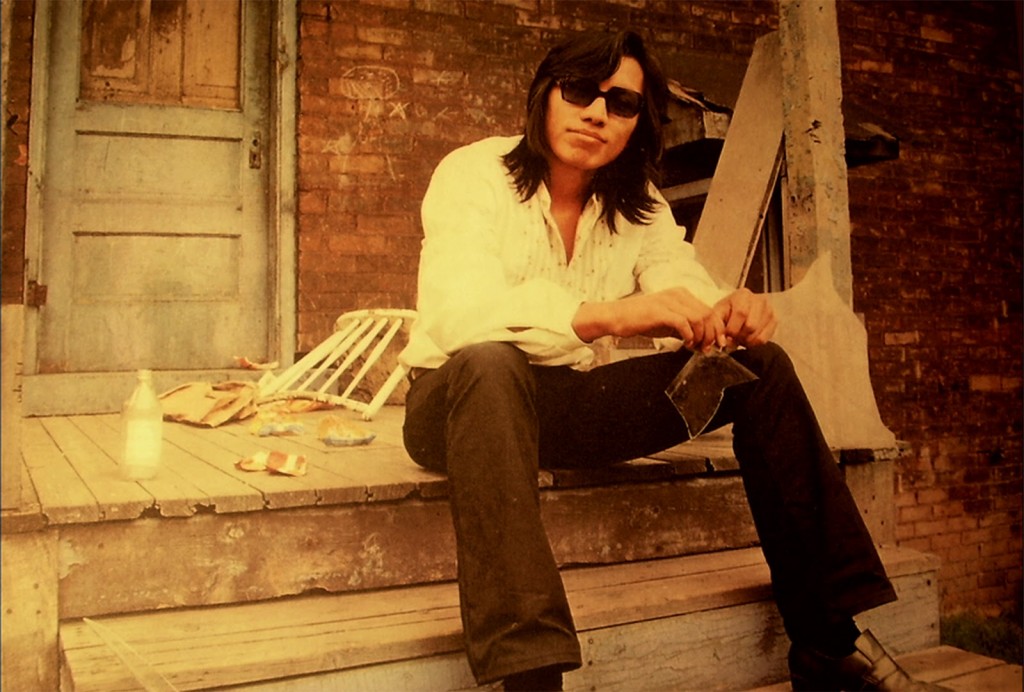

On August 14th, a funny thing happened. 30-some years after the U.S. all but wrote him off, Detroit-born singer-songwriter Sixto Rodriguez played the David Letterman show. The spot is a beautiful little piece of television, an appearance sweetened by the hosts enthusiastic endorsement, and with Rodriguez, now 70, sounding as soft and elegant as he did when the track was first recorded in 1969. Backed by strings and a horn section, the song Crucify Your Mind, comes off clean and brilliant, Rodriguez a master in his element. The question for most people, though, was, “Who the hell is Rodriguez?” because in 1970, his album, Cold Fact, sold less than a dozen copies in the United States.

There’s the rub.

The Letterman show marks the musician Rodriguez’s first nationally televised appearance stateside and by far his biggest gig to date, at least for American audiences. In fact, up until a few months ago when festival buzz surrounding Malik Bendjelloul’s documentary, Searching For Sugar Man, started making it’s rounds, Rodriguez was still pretty much unheard of in the U.S. On the other side of the planet in South Africa, though? Forget about it; the man’s a bigger household name than Elvis or The Beatles.

How this could happen, how a Motown-era inner city folk singer from Detroit could be completely unknown in the U.S. while simultaneously serving as a counter-cultural tool and political instrument in Apartheid-era South Africa, unbeknownst even to him, is more or less the subject of Searching For Sugar Man. It’s the mysterious story of Rodriguez, the man who in America should have been big, who was all but set up to be the next Bob Dylan, and who just wasn’t. And it’s a redemption story for a guy that shouldn’t have needed redeeming, that it was us that needed redeeming, and it just took a while for everyone to figure that out. There isn’t a guy on the planet that deserves recognition more than Sixto Rodriguez, and Searching For Sugar Man effortlessly convinces you of just that. Middle Western had the chance to speak with Rodriguez in the lead up to his Letterman appearance and the opening of Searching For Sugar Man, which begins showing today at the Edina Cinema.

Middle Western: I wanna ask you about Detroit to start, you were born there right?

Rodriguez: Yes sir.

MW: Did you listen to a lot of Detroit musicians growing up that influenced you?

R: We have a lot of radio stations in Detroit, so we get a lot of product coming up and influences from all over; so I’m attached to the music scene in Detroit or lack of it at times. The playlists have been those kinds of playlists for 30 years. I think that’s an exaggeration, but I think there’s going to be a turnover soon and other people are going to get played. Yes I do listen to Detroit music; you can’t get around it. But after 30 odd years of some of these playlists it’s just [sighs] . . . But when you have that kind of reputation like Detroit, even when Japanese tourists come in, they want to hear that stuff you know, and I’ll grant them that, and it’s good material there’s no debate about that.

MW: We’ll I mean, for example, Son House is from Detroit.

R: Yeah, and so is Little Willlie John and I do a Little Willie John cover. A long time ago CKLW had a radio show, a dance thing, and that’s where I saw the Stones when they first came out in ’62. And they would come through Detroit; a lot of bands would come through Detroit just to say they had been through there. It’s got a wild history and a lot of music. Bob Dylan’s from Minnesota, you know. I’m from Detroit, you gotta be from somewhere, I’m from Detroit.

MW: Did you listen to a lot of Bob Dylan when you were starting out and recording Cold Fact?

R: Sure, the protest songs for sure. Dylan’s Masters of War, Paul Simon’s I Am a Rock, Neil Young’s Ohio describing the Kent State protests where they burned their draft cards. In South Africa they had conscription, too, and they mimicked the effort.

MW: What did you think when you heard for the first time that your music had been used as a counter-cultural tool against Apartheid in South Africa?

R: I didn’t believe it, I didn’t really believe any of it, that I was anything in South Africa until Sugar, until [Sugar] Siegelman, he came to Detroit and showed me a CD. That was impressive to me and then to think that it was being published overseas, that was even bigger. They all came down when I toured in ’98, and I knew that it had to be real because they knew the lyrics. It was pretty amazing.

MW: Do you still play the same two albums or do you write any new material?

R: Oh yeah, any musician is like a writer; he’s not going to tell the same story over and over. It’s a living art and so yeah I write and I keep up with current music. I like Paolo Nutini, the Scottish-born Italian musician. I asked him up on stage and we’ve been mixing it up a lot you know.

MW: Do you think this second chance that you’ve gotten musically is some sort of karmic righting of the universe?

R: Well that’s an interesting term, “karma.” In what way do you mean?

MW: Like the universe is reaching down and righting the wrong.

R: Well I don’t know if it’s karma but it’s certainly something close to it. I also have to include a lot of luck. Strangers have helped me out, you know? The people who found me, the people who reissued the music, they were just strangers, so maybe it’s karma or I’m just a lucky guy, or someone around me is real lucky and I’m with them.

MW: In that period where you had stopped touring in the ’70s and ’80s, were you still playing music?

R: Well I never really toured. After the albums were out I did two tours in Australia in ’79 and ’81 and they were pretty huge tours, but after that I just pretty much stopped.

MW: So you had a following in Australia?

R: Yes I do. The way that happened is that the music was bootlegged from South Africa to Australia. There’s a DJ named Holger Brockman who played me after midnight on this radio station, Triple J. So that’s how I broke into the Australian market, but after that nothing happened for 20-some years.

MW: When you look back on that time, were you writing new music?

R: No, I was pretty much just doing construction, demolition of houses and buildings, so that’s what I was doing. What I do is I knock out all the walls and ceilings and floors, and then it’s ready for the plumbers and electricians, that kind of work.

MW: You’re done with that now though, right?

R: You never throw away your work clothes. Roofs always need repairs, or new roofs need to be installed, and it cuts costs, you know? Do it yourself, that kind of thing.

MW: Do you like that kind of work? Do you like doing it?

R: Yeah it’s invigorating work, you know, there’s no shame in hard work, and you should pull it close to you, whatever it is. The work teaches you.

MW: Do you think that there’s something about doing that kind of work that helps your music?

R: Well yeah, there’s the Chinese proverb, “A busy bee knows no sorrow,” you know, it’s that kind of thing. I think it’s good to stay active, and I’m politically active, too, I describe myself as a musical political. I vote for Obama; I think he’s closer to representing what I’m about, as opposed to the Teflon politics of the Republicans, and it’s my choice for sure. Issues like police brutality, we have that a lot in Detroit, Kelly Thomas beaten up by police, and it’s happening all over the United States, in Utah, in L.A. I’m not putting down the cops, I’m just putting down their techniques. I’m for social organization, but how about a little justice. It’s picking on the little guy.

MW: Do you think that’s what your songs will always be about then?

R: I think so.

MW: Kind of music as journalism?

R: I think so. The love themes are eighty percent of music, and I like that. I can write a ballad, but the protest genre is what I’m good at.

MW: What did you think when you saw the movie? Was it strange to see yourself on camera?

R: Yeah, the parts I like are the parts with my daughters, they become screen stars, so I like that part. I like the way he researched the subject and asked the questions about this and that.

MW: Do you think that the movie has invigorated you to get back out into the world and try to make a difference through music?

R: Yes. It’s excited my music career. We’re basically following the screenings with Q&A’s, and I’m doing gigs. I’m gonna be doing the David Letterman show August 13th.

MW: Who’s your band now?

R: Oh man, I got a dozen bands.

MW: Is it going to be one of the South African groups?

R: No I wanna bring youngbloods in, so I can teach them the experience, just like how they showed me stuff. I got an Asheville, North Carolina band I might try up there. And it’ll be great for them. You know, I was given the experience of so many good things, I got studios and things and I think that’s what the business needs is youngbloods. Power to the people.

MW: Do you think that things have happened that are good for you recently because you kind of stayed optimistic throughout?

R: Oh yeah.

MW: I mean to say, did you stay optimistic throughout? When you stopped touring and stuff were you sad?

R: In this music business there’s rejections and set backs and you have to be prepared. There’s no guarantees in music so you have to be conscious of that. It’s not without some tests.

MW: If you could turn things back, and say instead of stopping and then being found you instead just sold a modest amount of records and enjoyed a modicum of success that would have kept you as a working musician throughout, would you choose to have it be that way? Or do you prefer the way things happened now, where you have a magic trick that happens? Where it turns and there’s a twist at the end? If you could do it over again, would it play out as it has now?

R: My plan, was that I was going to record and I was gonna sell some records and get some money and then get some bigger rooms and go from there. I don’t think you ever enter into any of these things really knowing what’s going to happen, though. You get a general sense, but I don’t think you go in knowing. You adapt to the changes, and it’s okay the way that it’s happening now. We all want to be something, but I think you have to become something, you have to work at it. And who knows about tomorrow, you can go into things and try to be prepared, you can plan and want it, but who knows? What you said before, that word Karma, that’s a good way to think about it.

SEARCHING FOR SUGAR MAN

Directed by Malik Bendjelloul. Starring Rodriguez, Malik Bendjelloul. Running time: 86 minutes. Rated PG-13. Photo courtesy Red Box Films.